The Shell - Part II: Some UNIX details

Contents

5. The Shell - Part II: Some UNIX details#

|

5.1. Brief Recap#

The OS kernel provides a core set of operations, system calls, that permit a currently running user program to work with various types of files and to start new running programs, processes, from binary executable files. The UNIX systems provide a terminal orient, shell program that reads and executes command line . The shell can serve as a human-oriented, interactive interface, to the capabilities of the kernel. A core feature of the shell is its ability to located and run executable files as external commands. When we create new terminal windows, the UNIX OS starts a new independent shell process, whose standard streams, are connected to the terminal via a special device file type. In this way, each new terminal gets us a new shell process that we can use to execute command lines.

To provide additional flexibility and control the shell goes through several steps to process a command line. This includes nine different expansions. As part the command line syntax of the shell it provides us with the ability to control the Input/Output (I/O) of the command to be run, in the form of re-directions. More generally, the UNIX I/O model, is one of “files” and “streams”. The kernel provides operations such as open that allows a process to attach an existing, or new file, as a stream. A process can have many streams attached to it. The kernel maintains a file descriptor table, for each process, the entries track streams attached to the process.

A process uses an numeric index of file descriptor table entry to read bytes from or write bytes to a particular stream. In turn, the bytes will come from or go to the file that the stream connects the process too. The numeric indexes are often called file descriptors. The file descriptors, 0 - standard input, 1 - standard output, and 2 - standard error have special meaning as UNIX programs will by default use these as there source of data and where their normal and error data is sent. Various re-directions operators let’s us setup the streams that a command will have open before it begins to run.

The kernel provides a special, pipe, file type. A Pipe allows two processes to communicate in a coordinated way. Where one process can write to the pipe and another can read from the pipe. The kernel takes care of the details to ensure that the two processes synchronize correctly so that no data is lost and the processes will wait as needed. Exploiting pipes the shell provides the ability to create pipelines where several commands can be chained together. The chain is formed from left to right with the | symbol separating the individual simple commands. The standard output of the left command is setup to the standard input of the right command.

Using the abilities of the kernel the shell lets us not only run external commands as Synchronous, child processes of the shell, but also Asynchronously. By default, when we run external commands, the shell will wait for the newly started child process to finish before it goes on to read the next command line to work on. However, using the background operator, &, we can tell the shell not to wait, but rather start the command as a background child process and immediately continue to the next command line.

Various information is provided by the kernel and shell to new processes that are started. Exported shell variables, “name=value” pairs, called environment variables, are passed to newly created processes in addition to any command line arguments specified by the command line. Copies of the open file descriptors and the current working directory of the new processes are inherited from the parent shell’s values.

When processes exit, they provide an exit status value, in the form of an integer, to the kernel. The shell, as a parent of the child processes, it starts to run the external commands, the shell gathers the exit statuses. The UNIX convention, is that an exit status of 0 means success and a non-zero exit status means some form of failure. The shell lets us examine and use the exit status of external command to create various programming structures such as conditionals, if statements and loops.

Finally, in addition to supporting interactive use, where the shell waits for the next command line to be entered by us at the terminal, the shell program can be started with an argument that is a shell script file from which it will read the command lines to execute.

5.2. Overview#

In this chapters we will round out our understanding of the core concepts that the running software of a computer system is built around. Continuing to use UNIX as our example we will introduce the idea of users, privilege, permissions and credentials. We will then revisit Files and Streams along with Processes. As we go along we will both introduce UNIX shell commands that let us explore the concepts and we will expand our view of what is going on in the kernel. Finally we conclude by putting all the pieces together to provide a more detailed view of a running UNIX system.

5.3. Multi-User Operating Systems#

One of the defining features of UNIX is its origin as an operating system that allows multiple people to “securely” share, and use, a single computer, at the same time. UNIX’s popularity as the operating system used on the server computers of the internet have put its model and mechanisms for sharing a computer securely, at center of modern computer security. Much of what we hear about on the news and see in movies when it comes to security will often involve UNIX systems in one way or another.

Our goals in this section is to introduce the core terms and ideas that extend the notion of having multiple running programs, to having them potentially associated with different users.

5.3.1. Multi-programming/tasking#

Given what we are familiar with on most of our “devices”, we might take it for granted, that computer run-times support several running programs at the same time. However, this is not the only run-time organization for computing systems. In the past, operating systems for personal computers, such as DOS focused on running a single program/task at a time. The software that forms the operating system “kernel”, for such single-tasking run-times, are generally much simpler, and require fewer hardware features. To this end when their is no need for multiple processes, as is the case today, on the simple computers that are embedded in things like smart light bulbs or buttons, we continue to use single-tasking run times.

Note

An example, of a single tasking runtime, that you might be familiar with, is the Arduino run-time. The original Arduino boards such as the UNO are very simple with respect to the way the run-time is organized. A single application, program, is written, compiled and uploaded to the board. The “bootloader”, such as optiboot along with the libraries of software that come with the Arduino software development environment act as “library OS”. Where, where the bootloader enables the application to be uploaded on to the device and start the application running. The included libraries provide a set of calls that make it easier to make use of the hardware features of the board such as controlling and interacting with buttons, lights, motors, displays etc.

5.3.1.1. Multi-Processing#

Run-times that are designed to run more than one program at a time are generally referred to as multi-processing or multi-tasking systems. Typically, on such systems several running programs can be started at the same time. Beyond the basic ability to start several, concurrently running programs, systems can vary in a great deal as to the level of transparency and independence the running programs have with respect to each other and the operating system software.

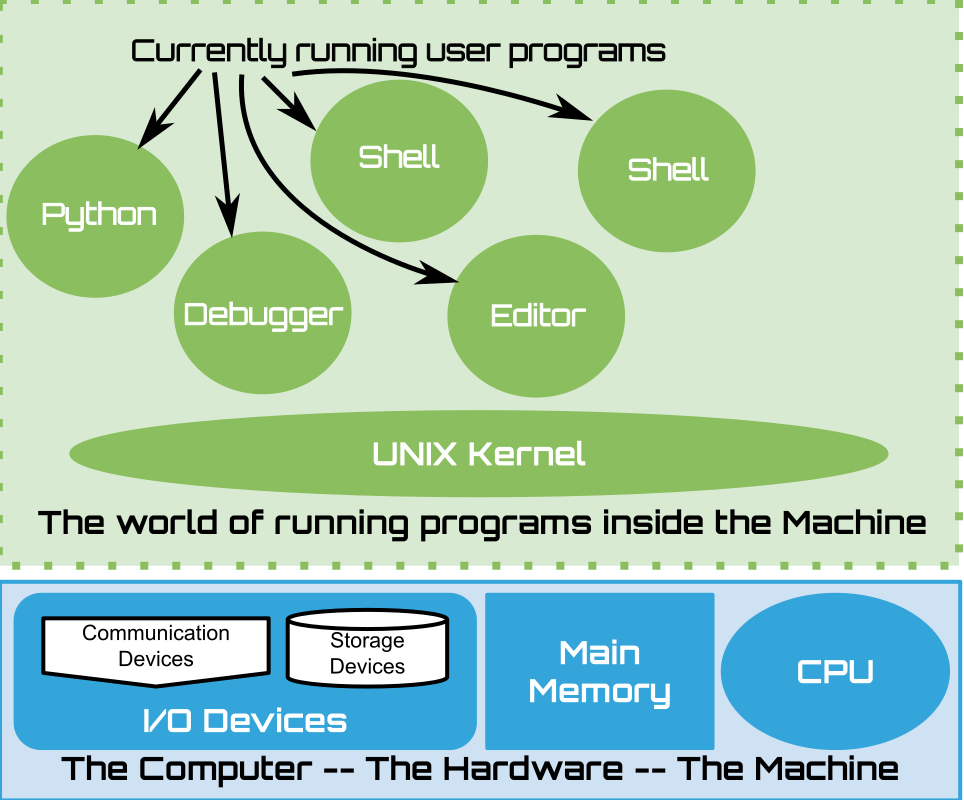

Clearly, UNIX is a multi-processing system. UNIX is built around the notion that an individual process should largely be able to ignore that it is sharing the computer with other processes. As a matter of fact, a program written to run on UNIX can be developed as if it was running on the computer alone, along with the kernel. It is the UNIX kernel’s job to ensure that this illusion of isolated use and independence is maintained.

Operating systems such as UNIX work very hard to try and ensure that processes cannot interfere with each other. By default processes are independent and cannot look “inside” another process or modify the behavior of another process. This includes the kernel. A process, cannot look inside the kernel or modify the kernels behavior. This ensures that even if one program is buggy the other processes and the kernel will not be affected by the buggy program. As a simple example, consider a program that accidentally has an infinite loop – loops forever not doing anything. Running such a program should not make the computer unresponsive or stop other running programs from executing correctly. The operating system’s kernel, must be carefully written and must make use of various hardware features, to enact this level of isolation. The goal is to ensure that the kernel is written to ensure that when running the kernel and processes are protected from the actions of any other process.

5.3.2. Multi-user#

In addition to running multiple programs at the same time, operating systems can be designed to share a computer across several different users. In the early days of computing this was the normal model. Computers were large expensive devices and inherently needed to be shared to be cost effective. The UNIX design is deeply influenced by its history as an operating system for computers shared by many independent users.

To understand this let’s take a moment to consider the opposite model – personal computing devices such as early Personal Computers (PC’s) and today’s Smart phones. In these cases, each user, owns their own device. All the software and data on the computer belongs to the physical owner of the device. In such cases, the operating systems need not support the idea of the device being used by several users and thus does not need to protect or hide information. There is one owner, who is also the only user of the device, and has complete control. On such systems, protecting running processes and the kernel is still a useful property. It helps avoid bugs or mistakes from crashing the system to the point where it is not usable or information is lost. However, more complex ideas like independent user accounts and files are not a necessity.

In contrast, UNIX was designed from the beginning to support a “multi-user” environment. So in addition to supporting the execution of multiple processes the system also needs to ensure that the processes, software and data of one user can be isolated, protected and even hidden from other users. In other words, the owners of a computer and the users of the computer need not be the same people nor should they have the same “rights” to do certain things. To this end UNIX developed various ideas for allowing multiple “user accounts”. Where the system supports the ability to isolate the processes and information across user accounts. Additionally, UNIX has a flexible model that also allows users to exploit the fact that they are on a shared system and selectively cooperate by sharing processes and information if they want to do so.

Regardless of supporting flexibility to cooperate and share information across users, UNIX must always ensure that the kernel is protected from all user processes and can never be, either intentionally or accidentally, compromised. After all, given the that the kernel is responsible for ensuring that processes are protected from each other if it can be subverted by an arbitrary user that user can then do anything they want with respect to the file and processes of other users.

As we will see in UNIX there is a special user, the root user, that in some sense represents the owner of the system and has the rights to create, modify and remove users accounts. The root user even has sufficient rights to comprise the kernel and as such access to this user account must be carefully protected. This might seem odd at first to have such a powerful user, but such a user is required to install the operating system and updated it as needed.

Note

So while UNIX started its life as an operating system for computers shared among several users, today it is also used on personal computing devices, such as laptops, tablets, smartphones, e-readers, watches, etc. It should not be hard to see that a system designed to support several users can easily be used by a single user by simply not creating multiple user accounts. Further using an operating system that has support for multiple users on a device used by a single user has the several advantages. One by creating an account for your daily work that does not have rights to modify all the files and information of the system can avoid one from making catastrophic mistakes that could result in crashing the system and looking data. Further if you do decide to share your devices with someone you can easily create a separate account for them and they will not have access to your personal data.

Note

The associated Jupyter software environment of this book runs in what is called a Linux container. It provides a reader with access to what is effectively a private single user Linux UNIX computer. Once you login into the JupyterHub service and you start your “server” the cloud service starts an independent UNIX user environment, a container, for you with on top of a UNIX kernel. This is an isolated and independent UNIX user environment that is for your use. There is a single main user who’s name is jovyan. Upon startup the software is configured to start a program called the “Jupyter Lab” server on your behalf. Once this software is running your web browser is directed to communicate with your Jupyter Lab server. This software sends to your browser the code (javascript) to allow you start terminal sessions. In this environment your identity is the jovyan user. The shells, bash processes, that are started for each terminal you create are automatically login as the jovyan user. Think of this as a your personal UNIX system and we encourage you to poke around and play!

5.3.2.1. Split, two-level, security model#

So while many independent processes can be concurrently running a more fundamental separation of the runtime exits – that between the kernel and all “user” processes.

5.3.2.1.1. Privileged (Kernel)#

As we have seen, the kernel is an ever present part of the runtime structure of a UNIX system. When the computer is booted the kernel is started and at least one user process is launched. After this many other user process can get started and be terminated. No matter how many or how few user processes exits the kernel will always be present. It is constantly taking care of many details of keeping the computer running. It is constantly monitoring and responding to the activity on the I/O devices such as terminals, networks, directly attached keyboards, etc. Further more, as we have seen it is fielding requests for its system calls from the currently running processes. For that matter, it is also ensuring that each currently running processes is getting its chance to execute. The kernel makes use of various special features of the hardware to both ensure that the processes stay isolated and to directly access the various devices of the computer.

To enable this separation and control the kernel must run in a special mode of the hardware that gives it access to all the advanced features it needs. We think of the kernel running in a special hardware enabled “privileged” mode. Thus we think of the kernel as the “privileged” software where it has access to the capabilities of the hardware that processes do not. In the next Part of this book, when we delve into what exactly the software of a program is and how it interacts with the hardware, at that point we will be able to more precisely understand what “privileged” mode is.

Note

While the UNIX runtime model is designed around a simple two level model of hardware enforced privilege the hardware itself might offer richer models that support several modes or “ring” of privilege/protection. Despite this the UNIX model only requires two and its simple model has ensured that it can be widely supported on various hardware systems.

5.3.2.1.2. Non-privileged (User Processes)#

In contrast to the privileged mode that kernel software runs in all processes run in a non-privileged mode. In this mode if they attempt to directly do a privileged operation such as directly accessing the hardware that enforces privilege the hardware will stop the process and hand control over to the OS kernel. As part of this the hardware will switch into privileged mode and let the kernel decide what to do.

In this way all processes are considered to be operating in the same non-privileged mode which we simply refer to as user mode. So we refer to all processes as user mode execution. On top of this simple two level model, kernel and user, the kernel must build up a mechanisms for distinguishing the processes and files with respect to individual users.

Given that all processes are started by the kernel and that all processes make calls to the kernel to make use of files the kernel can create distinction between the processes as belong to particular users by maintaining internal information. Using this information the kernel can permit or deny access by allow a call made by a process to succeed or fail.

At a high level the distinction between users, is as simple as writing the kernel software to conduct tests on every system call. The tests confirms if the user of the process making the request has the permissions to do the requested operation. If it does the operation is allowed to proceed and if not the operation is denied and the system call returns a failure to the calling process. Much of what follows is adding details on how this high level idea is translated in practice.

Note

In the diagrams we use to visualize a running system when we place items within the boundary of the kernel it is important to remember this interior content is not visible or accessible to the processes. The only way for a process to access something outside of itself is to make system calls (later we will extend this to include “exceptions”) to the kernel. The kernel then decides how to handle any given request from the particular process making the request. With this in mind we see that it is really the software of the OS kernel that create the view of the computer for a process. To help us understand the standard view the UNIX kernel presents to processes for interacting with the resources of the computers we will draw objects within the kernel boundaries.

5.3.3. UNIX users and groups#

In order to permit the distinction between users of the computer the UNIX kernel maintains a table of valid users. Each valid user is assigned a unique integer identifier called a user id (uid). To implement the notion of ownership and permissions we will see that resources will be stamped with uid’s to indicate what user owns a particular resource. In addition to the numeric uid UNIX keeps track of several pieces of information for each uid including a short ASCII human readable users name.

5.3.3.1. whoami and id#

Let’s run a few shell commands that display information about our current user.

bash.run("whoami")

The whoami command prints the human friendly user name of the process launched to run the command. As we can see our user name is jovyan. The id command can be used to print various information regarding the id’s of a process. Passing in the -u option tells id to only print the uid of the process.

bash.run("id -u")

id -u prints the numeric uid of our user.

To provide greater flexibility UNIX also support the notion of groups. The idea is that several users can be part of the same group and that a resources, such a files, can be made accessible by all members of the group not just its owner. To enable this model each user of the system, in addition to having a uid, has a “Primary” group id and potentially several “Supplementary” group ids. Like a uid a group id (gid) is a integer number that has associated with it group name. If a users has the gid of a particular group as either its primary id or within its set of supplementary groups the user is said to be part of that group and will have access to resources marked appropriately. More generally the collection of id’s that a user and process has associated with them are called its credentials.

We will discuss more details of how uid and gids are used with to grant or deny access to resources such as files below as we dig further into how the kernel represents processes and files with respect to credentials and permissions.

Now that we know about group ids lets use the id command to examine the uid, gid (primary group id) and the larger set of groups associated with a process.

bash.run("id")

Without any arguments, id, prints our uid, gid (gid of our primary group) and the full set of group ids that we are a part of. In addition to printing the numeric value for the ids the id command also displays the human readable ASCII name that is associated with the id (if it has been assigned one).

5.3.3.2. /etc/passwd and /etc/group#

As one can imagine the set of valid users and their id’s must be configured and maintained by the owner of the computer. To ensure that this information is available when the kernel is started UNIX, traditionally, reads the the information from two files “/etc/passwd” and “/etc/group”.

Let’s take a quick look at these files. Lets start by coping the contents of /etc/passwd to our terminal using cat.

bash.run("cat /etc/passwd")

Every line in the /etc/passwd corresponds to a valid user of the system. Traditionally several user are added to the system to for various administrative tasks and to run various long running services (“server” processes).

Examining this contents you should be able to find a line that corresponds to the id of our user. Each line is broken down into fields with ‘:’ separating the fields. The first field is the user name, the third field is the uid that has been assigned to the user, and the fourth the user’s primary gid. Additionally, a user’s entry will also store where their home directory is and what program to run as their login “shell”. With all this information the kernel can know who the valid users of a system are and how to get a initial process started for them when then access the system.

On our version of UNIX the details of the /etc/passwd file can be found in section 5 of the manual.

bash.run("man 5 passwd", height="10em")

As you can see there is no information in the /etc/passwd file regarding the supplementary groups a user belongs to. The only group information we see is the gid of the user’s primary group. The reset of the group information is traditionally keep in the /etc/group file. Let’s take a look.

bash.run("cat /etc/group", height="10em")

Like with users there are often man groups configured for various systems needs. Each line in this file is the information about a particular group. This information includes the group’s name, gid and the list of users (identified by their user name) that belong to the group. The details of the /etc/group file can also be found in section 5 of the manual in our version of UNIX.

bash.run("man 5 group", height="10em")

Given that our system is configured for use by really just one user “jovyan” both the /etc/passwd file and the /etc/group file is rather sparse and not very interesting. If you have access to a UNIX system that is used by many people take a look at these files they will be much more interesting.

Hint

Traditionally, the /etc/passwd file also contained a version of a user’s password and a program like “login” (see man login) would be run when a user attempted to start a new interactive session with the system. “login” would prompt the person attempting to access the system for their user name and passwd. login would then look up this information in the /etc/passwd file if it matched a line then login would start the specified shell program to allow the user to interact with the system. If the supplied information did not match any line in the file then the user would be denied access.

To obtain a valid user account, a line in /etc/passwd, for which you know the associated user name and passwd, you need to ask a system administrator who already has an account and the appropriate permissions to “write” new entries into the file. Security hinged on the administrator “knowing you”, not making mistakes and not users protecting their passwords.

Given that all users can read /etc/passwd the passwords stored in the file needed to “encrypted” so that existing users could not simple use /etc/passwd to obtain the passwords of other users. To this end, login after receiving the password from the person attempting to access the computer, would apply the same “encryption algorithm” to the password provided and then see if the encrypted version matched what was in the file. The un-encrypted version of the password is often called the “plain text” version and is usually just a normal ASCII encoded string.

As you can see this means that the security of the system also depends on the encryption method and how hard it is to “break” it. That is to say can you use having access to a user name and the encrypted version of the password to “figure out” what the un-encrypted version is. If so you could provide this information to login and gain access to the computer as that user.

Additionally, you can see in this model, if anyone can “peek” at the communication of the plain text password then they don’t even need to do the hard work of “breaking” the encryption algorithm. To this end the security of the physical connection of devices like terminals to the computer on which the bytes of being entered are transmitted to the login program as susceptible to attack. For that matter even the terminal is a point of vulnerability. If someone modified the terminal to record the key strokes and send them else where they could obtain your plain text password!

While things have gotten more complicated today the basic idea of identifying yourself to by a user id and password to a computer system still is very common. And while the process looks different many of the same security concerns, attacks and vulnerabilities still exist.

Note

Some versions of UNIX can now use other files and databases to either override or extend what is in the traditional /etc/passwd and /etc/group file.

5.3.3.3. The root user#

UNIX reserves the zero uid for a special purpose user called the “root” user. The 0 uid is allowed to access any resource it likes not just ones owned by it or that are marked with a group it is part of. In other works the “root” user is a “super-user”. The root user is capable of accessing any files on the system, changing and modifying the information of any user (including changing their password) or group. The root user can potentially, even run commands that give them access to change the kernel.

As you can see protecting access to the root user is very important to keep a UNIX system secure. That being said we generally always need some user who can “fix” things!

Hint

A common mistake people often make when they obtain their first UNIX computer, that they have full access to, including root, is to use the computer using the root user. They tend to think, “Well this is my computer, so I will just use the root user account to do all my work, as I will then be able to changing anything I like”. This is a very bad idea, all of us who take this short cut eventually regret it. The likelihood of making a mistake and deleting files or making changes that “break” the system is very high. You are far better off creating a normal user account that you use for your daily work and only use the “root” user account when you need to do something that requires the extra permissions.

5.3.4. Kernel View#

Now that we have a working knowledge of UNIX user and group ids lets conceptualize how they relate to the kernel. To do this lets start lets use a conceptual visualization of internal table of the user information that the kernel will load from the passwd and group files when it start. While in reality the details may be different visualizing the information can help is better understand how the things we do at the shell relate to how the information and maintained in the kernel.

5.3.4.1. Traditional: User Group Credential Model#

5.3.4.2. Modern: Capabilities#

5.4. Revisiting UNIX Files and Streams#

5.4.1. Types of Files#

5.4.2. Meta data#

5.4.2.1. Ownership and Permissions#

5.4.2.2. Operations and Permissions#

5.4.3. Kernel View#

file as objects in kernel

regular and special